After my ride across Honshu last year, I have wanted to try a few other WUCA (World Ultracycling Association) unsupported record attempts, to try and get this concept established in Japan.

Since I did my unsupported Honshu WUCA record ride, supported/crewed WUCA records have been set in Japan by 32 yr old Yaofeng Cheng, a Japan resident woman rider going North-to-South and 35 yr old Australian Jack Thompson going South-to-North, in each case including Kyushu and Hokkaido as well as Honshu. But no one has duplicated the unsupported Honshu-only ride. Of course, Thompson, who did Japan South to North in just a smidgeon over 5 days, has a number of other records around the globe, and rides complete with sponsors and a full crew. No desk job. It looks as if Yaofeng Cheng had a full crew of Japan Audax riders and other cyclists with her.

Anyway, this year I am not in as good cycling condition as previous years. I never got in my SR series this Spring, having missed several due to schedule issues, and DNFed (recurring stupid mechanical issues) my 300km ride, and then DNF'ing a Golden Week 1000km ride (lack of preparation mostly).

So I have had limited ambitions for the Fall. I have tried to build up some more base since August, at least, in order to try a shorter record attempt.

WUCA also registers records for major city-to-city pairs, and for going across a region, or state/prefecture. I thought -- why not go across Tokyo Prefecture. Set forth below is an extended version of my "narrative" ride report to the WUCA.

-----------------

Start. I started at 10:50PM on October 26, on National Route 411 at the Yamanashi border near the far western end of Lake Okutama. There is a small bridge over a gulley with a stream into the river. The Eastern side of the bridge has Tokyo border signs, while the western end has Yamanashi Prefecture and Tabayama Town border signs. I started just off the western end of the bridge inside Yamanashi.

Conditions

The conditions were near perfect for this ride.

I wanted to do this ride late at night to avoid traffic. The main challenge of riding across Tokyo Prefecture – population 14.1 million – is congestion. Many of the most direct routes are no fun to ride during the day, fighting with trucks and cars. The first third of the route to Oume is mostly rural and so congestion is not an issue, absent roadwork, but once you get into the city, congestion would add time to this ride and make it unpleasant. Late at night, with very low traffic volumes, it could be much faster, safer, and a lot more fun.

I spent an

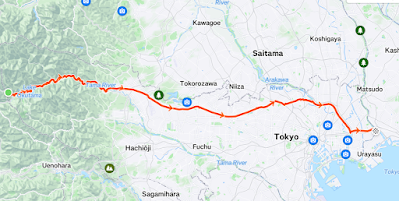

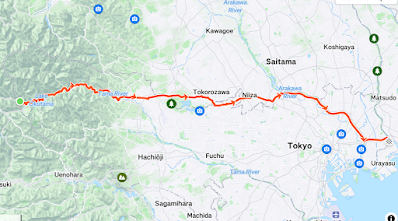

inordinate amount of time trying to figure out the best route. Should I go the straighest line 98.13kms?

( https://www.strava.com/routes/3273251512526534248 )

Or perhaps make a minor alteration and take Inokashira Dori into town - a fast, flat, straight, and low traffic alternative that I know well 101.67km? ( https://www.strava.com/routes/3283272140791505062 )

Or swing north and avoid central Tokyo to instead go down the Arakawa 102.98kms

( https://www.strava.com/routes/3273258823699968166 )

Or even go through Saitama (Tokorozawa ... Wako) and a longer stretch of the Arakawa to avoid traffic lights and take a very fast, dark Arakawa path 105.81kms?

( https://www.strava.com/routes/3283278143772050928 )

Or down the Tamagawa and in Meguro Dori ... to maximize the no-light stretch along the Tamagawa and then be on familiar roads through town 110.99kms?

( https://www.strava.com/routes/3283461428696622960 )

In the end, I opted for a compromise -- familiar roads, and a route with a slight dip to the South, around 103kms. Rte 411, then Yoshino Kaido, then Ome Kaido, then Shin Ome Kaido, then Rte 20 (Koshu Kaido) through Fuchu/Chofu and all the way to Shinjuku, Yasukuni Dori east to the Sumidagawa and R 14 beyond to the Edogawa.)

Strava Link

https://www.strava.com/activities/12751175085

I think that route worked out well. In town on Rte 20 and Yasukuni Dori then Rte 14, I could see the traffic lights far ahead, see the walk signal change to flashing green then red, accelerate or relax depending on whether I was going to make it. And when I missed a light, I decided to enjoy the brief respite. The only section where I got really frustrated by the lights and constant stop/start was on the stretch between the Imperial Palace and the Sumidagawa (Sumida River) – the old central Tokyo downtown.

I think a faster rider could do better with the route through Saitama then down the Arakawa. That is only a few kilometers longer and offers 25kms of nonstop time trial down the Arakawa. But I did not have time to vet it carefully for the stretches between Oume and Wako, and also, is it really a ride "across Tokyo Prefecture" if you take large stretches through Saitama. Somehow that does not seem in the spirit of the challenge, even if it would not violate the rules (I was told I could take any route, as long as the end points are clear).

The weather was fine -- warm for late October. It was 14 Celsius (57 fahrenheit) and cloudy at the start and this remained nearly constant (12~16 Celsius) even as I rode from the mountainous interior to the plain adjacent to Tokyo Bay. As I planned the ride, I was concerned that it might be quite cold at the start deep in the interior mountains, even this time of year. So I did not want to ride too late in Fall. On the other hand, the Tokyo weather can remain hot and humid into October and I did not want to ride it too early. I ended up with Goldilocks weather – just right!

There was a breeze from the NE at times – it felt a bit as if I was riding into a headwind on Route 20 around Chofu as the road turned from ESE to ENE direction -- but the breeze was not strong and never directly in front.

Why This Record

I wanted to do this to “lay down a marker” so that someone else will beat it. There are plenty of Japanese cyclists who could do it faster than I can, some much faster, some in my age group, some who ride recumbents, and many younger road cyclists. I hope this will encourage them to try.

Equipment Used

I rode my Pelso Brevet “carbon high racer” recumbent. I am slow climbing on the Pelso, but this was a largely flat and downhill course with very little climbing. I now have a 48-tooth oval single front chainring and an 11-50 rear cassette, with a 12 speed SRAM mountain bike derailleur, but it is otherwise set up the same as for last year’s long ride across Honshu.

Since the ride would be entirely at night I used my SP Dynamo hub front wheel, as well as a Busch Mueller Icon IQ/XS front light and several battery-powered rear lights. I experimented some with LED powered front lights, but could not get any to work as well as the dynamo-powered Icon IQ/XS. So it is a no brainer choice – set and forget – even with some very modest drag from the dynamo.

I rode in relatively leg-hugging running shorts, cycling jersey, wool short-sleeved inner layer, reflective vest and ankle bands, and running shoes with wool socks, with rain/warm gear stowed in my Radical Designs rear seat bag just in case.

Eat and Drink

I left home around 1PM and rode the 89.4kms (and 640m elevation gain) to the start.

|

| A quick stop at Y's to replace a bell that broke a few kilometers beforehand. |

|

| A cloudy, hazy, and warm (for late October) afternoon climbing from Oume. |

|

| The start of Yoshino Kaido, at Kori. I will head down there tonight. |

|

| It was after 6PM and pitch dark by the time I approached the west end of Okutama. |

I was feeling pretty drained even before leaving home from lack of adequate rest over the past week, and I could feel some burning in the legs at times as I climbed toward the start at Lake Okutama. My Garmin smart watch told me that my "body battery" was empty already that morning ... as it had been the day before. So doing such a long ride to the start was not ideal, not at all ideal … but I had planned to do this effort entirely alone, the Pelso is not easily carried on Japanese public transit, and the logistics of leaving a car at the start and returning to pick it up later were not great, so I just rode to the start and then home from the finish.

|

| The minshuku where I rested, as it looked at 10:45PM. |

I booked a room for JPY3000 ($20) at a very basic inn very near the start. I arrived at 630PM and planned to leave around 1030-11PM. The inn seems mostly to host groups of hikers, who do their own cooking. They do not serve food, and most of the nearby restaurants (including Yagyu-tei where we often stop when we ride the west end of Okutamako) serve only lunch to passersby. So I knew I could not get dinner anywhere near the start. Instead, I ate (carbonara pasta, a rice doria, etc., etc.) on the way out, one stop in Oume and again at the 7-11 at Kori, and took some sandwiches and Japanese convenience store basics with me to eat after arriving at the inn.

The innkeeper and his wife were both in their 90s, and I was their only guest Saturday evening. I was quite impressed with the 93 year-old innkeeper who spryly walked up several flights of steps on the outside of the building to show me my room. I ate my sandwiches, rested and even got an hour of sleep. In this perfect weather I could have rested without an inn, but in any other conditions the inn would have been a lifesaver. And given my exhaustion I really needed some rest.

During the ride, I ate maybe 4 half-sized “Kind” nut/energy bars, some bite-sized 7-11 apple danishes, and a Snickers bar, with more similar food in reserve. I carried a 950mm water bottle with a mix of water and sports drink, and another 500mm water bottle in my bag. I felt somewhat de-hydrated from the climb up to Lake Okutama, so I drank a lot of water at the inn to try and re/pre-hydrate in the 4+ hours before the ride. Of course, I wanted to do this sub-4 hour ride without any convenience store or other stop to take on food or drink, and was able to make it. Ideally, I would have had a bit more sports drink with me, but the cool weather and nice downhill section early in the route meant I could manage without. My only stops were traffic signals, plus 2 quick bathroom breaks at roadside (a side effect of having drunk so much liquid before the ride).

Best Part

The best part of this ride was that probably 75% was on familiar roads, ridden in ideal weather and low traffic. I love riding in Japan at night when traffic is low. It helps to have relatively smooth and unobstructed roads and good lighting.

Hardest Part

|

| At the start ... very quiet, but there were actually some people around, and some cars driving along Lake Okutama late on a Saturday night. |

The start was really difficult. Lacking adequate rest, I felt drained, even after a couple hours of rest. The first stretch along Lake Okutama had me wondering if I should not just give up, relax, ride home, and try again another time. Every time I pushed it a bit, I needed to back off the throttle. But I recovered on the long downhill and so, by the time I needed to really start to work harder again on the remaining two-thirds of the ride, I felt okay.

|

| Entering Chiba, at the sluice on Kyu Edo Gawa |

Finish. I finished at 2:37AM on October 27, for 3 hours and 47 minutes. I finished just on the eastern side of the Kyu Edo River at the Edogawa Sluice. Tokyo Prefecture follows the Edo River and, after they divide, the Kyu Edo River, and this is the furthest east crossing into Chiba that I could locate. There is a wide cycle/walking path over the river here (on top of the sluice) that is closed to cars but regularly used by cyclists and pedestrians. Even at the end of my ride at 2:37AM on Saturday night, there were 3 younger men fishing off of the sluice and talking.

I chatted with them a bit, explained that I had just come from the Yamanashi border and was happy to get to the Chiba border. One of them said that there is actually a dispute between Tokyo and Chiba as to which of them controls the bit of land on the island at the east end of the sluice. ... but Google Maps, Yahoo Maps and others all show the border where I was standing as Chiba.

After the

finish, I stopped at a nearby convenience store for some food and a cup of

coffee, then rode back to and across the sluice, and home slowly. On the ride

home, I went right down the middle of the Ginza -- Chuo Avenue -- the bright

lights of the stores on even at after 3AM. The blocks are short and each one has a traffic signal, and they all turn red and green together. It makes for a nice effect ... but that is one street where it is impossible to time the traffic

lights!

|

| Approaching Ginza, at 3:30AM. |

This felt a bit odd to report this ride to WUCA. It was not my toughest ride this year, not my longest, and I am not in my best shape. But at least I've put down a marker and now someone else can beat it!